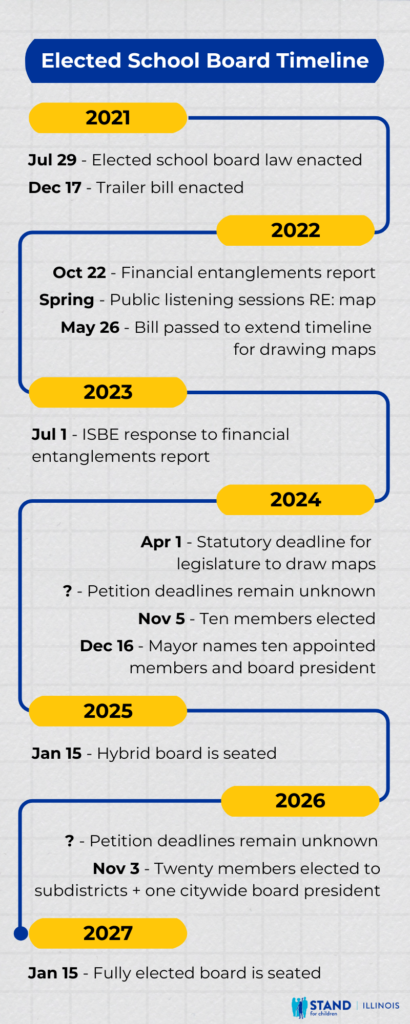

The Chicago Board of Education will undergo a dramatic transformation over the next three years as it transitions from a mayoral-appointed board of seven members, to a hybrid board of 10 elected and 11 appointed members, to a fully elected 23-member board. It’s a big change that’s coming up fast – so the clock is ticking for the legislature to finalize some pretty critical details. On Tuesday, the legislature began another round of listening sessions for input on the school board map. The second (and last, as far as we know) hearing is October 12[1]; then the legislature returns for Veto Session[2] October 24 and will have the opportunity to address some of these questions.

This blog series will feature three installments. Today’s post summarizes the law, the implementation timeline, and the history of school governance in Chicago and other Illinois districts. Next week, we will dig into elections – and some of the potential ramifications of skipping the Primary process. And finally, we will close with a blog that looks closely at school board compensation across the country, which is really deeply intertwined with another question: what is the role of a school board member? (If you have thoughts on either the compensation question or the role-of-a-school-board-member one, pop over to take our poll and share your thoughts…)

Summary of the Law

In 2021, SB 2908 (Martwick/Ramirez) passed, shepherding in Chicago’s new school board structure. At the November 5, 2024 general election, ten school board members will be elected to four-year terms, with one member from each of ten subdistricts. Elections will be nonpartisan. By December 16, 2024, the mayor will name ten appointed members – one from each subdistrict – to serve two-year terms beginning January 15, 2025. The board president will be appointed during the hybrid period and elected Citywide in 2026.

In the 2026 general election, a board will presumably be elected from each of twenty subdistricts – though the law is somewhat ambiguous about how the ten districts become twenty. (Will the ten districts be split in half to make twenty total or will a different map be drawn? Since the legislature and advocacy groups have so far only released draft maps of twenty districts, perhaps the twenty will be paired up to become ten?)

“From January 15, 2025 to January 14, 2027, each district shall be represented by one elected member and one appointed member. After January 15, 2027, each district shall be represented by one elected member.”

105 ILCS 5/34-3

A trailer bill was enacted after the initial legislation passed to make several changes, including explicitly banning board members from receiving compensation and removing the requirement that mayoral appointees receive City Council approval. The General Assembly extended the date by which subdistricts needed to be drawn when they failed to reach consensus by the initial deadline of July 1, 2023. State law now requires the legislature to draw the subdistrict map by April 1, 2024,[3] though we expect this issue to arise during the upcoming Veto session.

Candidates for the board cannot be employed by or hold significant contracts with the school district. Members must collect 250 valid petition signatures to get on the ballot, though the timeline for submitting those signatures is not specified. The board president must collect 2,500 signatures.

There are questions that have not been addressed in the law to date; perhaps the mapping legislation will also provide answers to some of these open questions. For example, when are petitions due? What’s the alternative to a primary that would safeguard against an extremist candidate winning with a fraction of the vote in an extremely crowded field? Are there are campaign contribution limits that should be added?

History of CPS School Governance

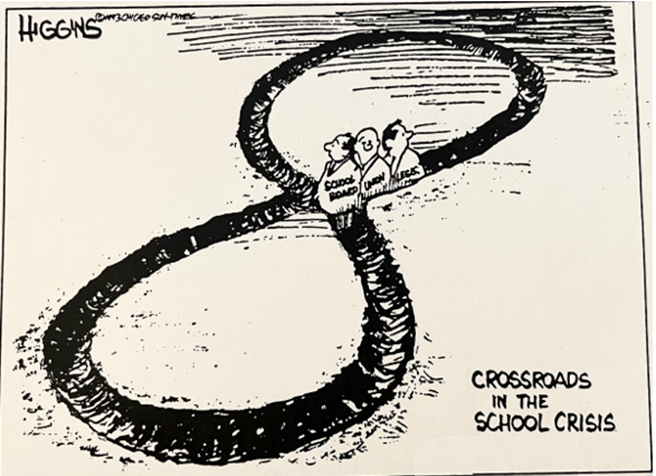

Chicago has a long history of innovative governance initiatives, amid a long history of perennial school finance crises, which were often solved with short-term funding band-aids that inevitably caused the cycle to continue. If you want to skip this section, this Chicago Sun-Times cartoon by Jack Higgins on October 20, 1993 provides a concise summary:

If you’re still reading along with us, let’s go back to 1980… CPS relied on short-term borrowing to make payroll, but when investors learned that the district was spending from its debt service fund, there were zero bids on CPS’s attempt to issue more bonds. The legislature intervened, creating a School Finance Authority to oversee CPS budgets, enabling CPS to issue short-term bonds, and diverting an existing 50-cent tax levy to repay them. The School Finance Authority (SFA) meant that after 1980, schools could be shut down either by the SFA failing to balance the budget or by a union strike.

A 19-day strike in 1987 (which was the eighth strike since 1970) resulted in a groundswell of parent activism, with vocal community members coalescing around finding a long-term solution.

This movement led to a historic governance change in 1988: the creation of Local School Councils (LSCs). LSCs are school-based governance councils consisting of teachers, parents, community members, and other school staff who are elected to their seats. Their major responsibilities were hiring the school principal and allocating school-level discretionary funds, although legislation later removed this decision-making power from underperforming schools. This was the largest decentralization effort in any school district in the country.

The LSC legislation also created a nominating commission process, where 23 parent councils across the city would nominate board members for the mayor to choose from for the seats on the Chicago Board of Education. LSC members take required hours of training and earn no salary. Title One funds that the district received were transferred to LSCs for their members to determine locally how that funding would be spent – a good move toward school-level funding equity, but a $260 million hole in the district’s budget.

In 1993, another crisis struck: the SFA ruled the budget unbalanced. A series of short-term court interventions kept schools open, but that was not a sustainable solution. The legislature stepped in and allowed CPS to issue two years of bonds, which would be paid back through freezing the Title One money that flowed to LSCs and diverting $110 million from the pension levy.

When those two years ended, the next fiscal cliff set in and it was time for another state intervention. But unlike the others in recent memory, this time the Republicans held the Governor’s Office and a majority in the State House and Senate. The 1995 shift in CPS governance brought a mayoral-appointed reform board of trustees of five members, which would be replaced by a seven-member mayoral-appointed school board in 1999. This posed an unusual dichotomy: highly decentralized governance at the school level with LSCs and highly centralized power at the district level. The 1995 reform law included many other provisions that gave the district unprecedented authority to maximize budget flexibility and, in theory, get the cycle of budget crises under control. In addition to the school board composition changes, the bill collapsed multiple tax levies into two streamlined pots, allocated state funding through unrestricted block grants, and narrowed the issues subject to collective bargaining. (Since then, the General Assembly has added back the pension tax levy as a separate funding stream, ended the Chicago Block Grant for most state grants, and put items back on the collective bargaining table.)

The next major shift in CPS board governance is scheduled to take place in 2025 when the 21-member hybrid board is seated, with 10 elected members and 11 appointees. In 2027, the fully elected 21-member board will take over governance.

School Governance in Other Illinois Districts

No other school district in Illinois has either LSC structures or a mayor-appointed school board. Nearly every other district has seven unpaid[4] school board members elected districtwide (such that all districts voters vote for several candidates from among whoever runs for school board). A handful of Illinois school districts elect their board members from among subdistricts, where the school district is mapped into seven areas and voters from within each elect their own board member who lives in that subdistrict. We found nine Illinois school districts that elect board members through subdistricts:

- Rockford SD 205

- Springfield SD 186

- Peoria SD 150

- Urbana SD 61

- Crete-Monee 201U

- CHSD 218 (SW suburbs)

- North Mac CUSD 34

- Bureau Valley CUSD 340

- W. Carroll CUSD 314

Several of these were mandated by a consent decree as a measure to encourage boards’ demographics to reflect the population of the district. We also found approximately twenty districts that allocate a certain number of seats to candidates in one county and another in remaining counties.[5] One district – North Chicago SD 187 – has remained under an ISBE-appointed independent authority since 2012, but has begun the process of transitioning to an elected school board, with a hybrid board beginning in 2025 and a fully-elected, seven-member board in 2027.

We’ll share Part 2 next week, where we’ll get into Election issues. If you have thoughts on school board member compensation, please head here to take a quick survey.

[1] Individuals who wish to provide comments can sign up for the October 3 or October 12 hearings.

[2] “Veto session” is a short window of time in the fall when the legislature reconvenes for the purpose of taking action on bills the Governor has vetoed, though they often take up other time-sensitive matters as well.

[3] SB 2123 (Morrison/Stuart) August 4, 2023 PA 103-0467

[4] State law prohibits school board members from being compensated.

[5] These districts include: Bloomington, Edwardsville, Belvidere, Charleston, Sterling, Manteno, Hoopeston, Mendon, LeRoy, Griggsville-Perry, Warsaw, Southeastern, Hiawatha, Hartsburg-Emdon, Murphy, and Ramsey.